This section of our NREMT study guide covers the Cardiology and Resuscitation portion of the NREMT exam.

We have it into different part starting from foundational anatomy and physiology leading to patient assessment, interventions for specific cardiac emergencies, and finally to the principles of resuscitation.

Part 1: Foundational Anatomy & Physiology

The Structure of the Heart

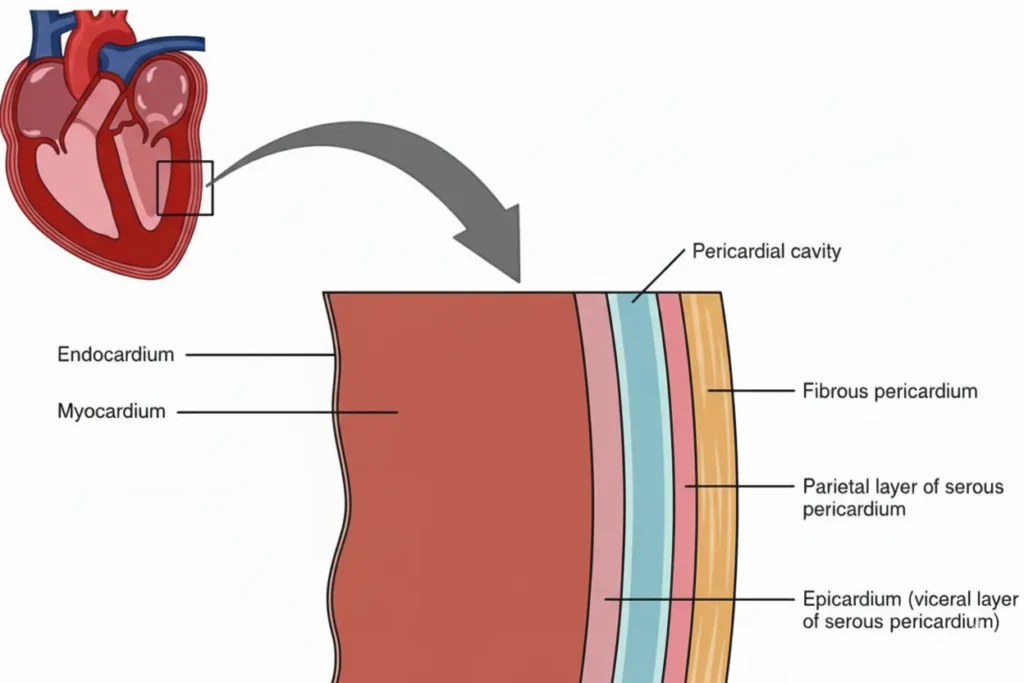

- Heart Wall Layers:

- Epicardium (Outer Layer): The outermost protective layer of the heart.

- Myocardium (Middle Layer): The functional muscle of the heart, responsible for the powerful contractions that pump blood. The thickness of the myocardium varies, with the left ventricle being the thickest since it has to pump blood throughout the body. An Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) primarily affects this layer.

- Endocardium (Inner Layer): The innermost lining of the heart chambers and valves, providing a smooth surface for blood flow.

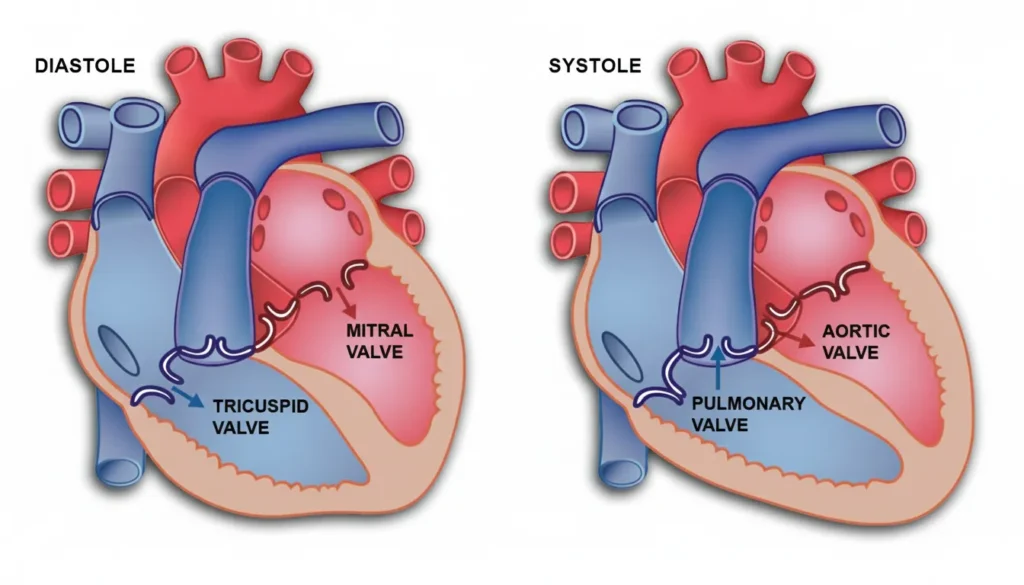

- Heart Valves: These structures ensure the unidirectional flow of blood through the heart’s four chambers.

- Tricuspid Valve: Located between the right atrium (RA) and the right ventricle (RV).

- Bicuspid (Mitral) Valve: Located between the left atrium (LA) and the left ventricle (LV).

- Pulmonary Valve: Located between the right ventricle (RV) and the pulmonary artery.

- Aortic Valve: Located between the left ventricle (LV) and the aorta.

The Vasculature

- Arteries & Veins: Arteries carry oxygenated blood away from the heart (except for the pulmonary artery), while veins carry deoxygenated blood toward the heart (except for the pulmonary veins).

- Capillary Sphincters: These are circular muscular walls that surround capillaries. Controlled by the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), they constrict and dilate to regulate blood flow through capillary beds, directing blood to areas where it is most needed.

The Concept of Perfusion

Perfusion is the circulation of blood within an organ or tissue in adequate amounts to meet the cells’ current needs for oxygen, nutrients, and waste removal.

- The Perfusion Triangle: For perfusion to occur, all three components must function properly. The failure of any one part results in shock (hypoperfusion).

- The Heart (The Pump): It should pump blood effectively at an adequate rate and force.

- The Blood (The Fluid): There must be sufficient blood volume to circulate.

- The Blood Vessels (The Container): The vessels must have adequate tone (resistance) to maintain pressure.

Key Physiological Concepts

- Vagus Nerve: A major nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system. Stimulation of the vagus nerve (e.g., straining during a bowel movement, severe pain) can cause a “vasovagal response,” leading to a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure, which can result in dizziness or syncope (passing out).

- Atherosclerosis: A disease process where cholesterol, calcium, and other substances (plaque) build up inside the arteries. This narrows the arteries, restricting blood flow and creating a rough surface where blood clots can form, leading to conditions like AMI and stroke.

Part 2: Patient Assessment

Initial Triage & Priority Patients

Rapidly identify high-priority patients who require immediate intervention and transport. These include patients with:

- Severe chest pain

- Poor perfusion (pale, cool, diaphoretic skin)

- Unresponsiveness or altered mental status

- Uncontrolled bleeding

- Pregnancy with complications

Vital Signs & Pulses

- Pulse Assessment:

- Check Duration: Should take no more than 10 seconds.

- Locations:

- Infant (< 1 year): Brachial pulse.

- Child/Adult (> 1 year): Carotid pulse for unresponsive patients. Radial pulse for conscious patients.

- Qualities:

- Thready: Weak and rapid.

- Strong: Normal.

- Bounding: Abnormally strong.

- Rhythm: Regular vs. Irregular.

- Blood Pressure:

- Systolic (Top #): The pressure in the arteries during cardiac contraction (systole).

- Diastolic (Bottom #): The pressure in the arteries when the heart is at rest between beats (diastole).

- Normal Vital Signs by Age:

| Age Group | Respiratory Rate | Heart Rate | Systolic BP |

| Newborn (0-30d) | 30–50 | 100–180 | 70 |

| Infant (1-12m) | 20–40 | 70–190 | 70–100 |

| Toddler (1-3y) | 20–30 | 80–130 | 80–110 |

| Pre-schooler (3-5y) | 16–22 | 80–120 | 90–120 |

| School age (6-12y) | 14–20 | 70–110 | 100–120 |

| Adolescent (13+) | 12–20 | 60–100 | 120 |

Key Physical Findings

- Jugular Vein Distention (JVD): Swelling of the jugular veins in the neck. It indicates increased pressure in the venous system due to blood backing up. It is a key sign of:

- Right-sided heart failure (CHF)

- Cardiac tamponade

- Tension pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism

Part 3: Resuscitation Principles

The timely initiation of resuscitation is the most critical factor in survival from cardiac arrest.

The Chain of Survival

- Early Recognition & Activation of EMS: Recognizing the emergency and calling for help.

- Early, High-Quality CPR: Immediate chest compressions to circulate blood.

- Rapid Defibrillation: The single most effective treatment for Ventricular Fibrillation (V-Fib).

- Advanced Life Support (ALS): Advanced airway management and medication administration.

- Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: Integrated care in a hospital setting to improve neurological outcomes.

- Recovery: Physical, social, and emotional support for the patient after survival.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

- When to Start: Initiate immediately for any patient who is unresponsive, pulseless, and apneic. For pediatric patients, begin CPR if the pulse is less than 60 beats/minute with signs of poor perfusion.

- Key Metrics:

- Rate: 100–120 compressions per minute.

- Depth: 2–2.4 inches (5–6 cm) for adults and children.

- Ratio (Adult): 30 compressions to 2 breaths (30:2) for both 1 and 2 rescuers.

- Ratio (Child/Infant): 30:2 for a single rescuer; 15:2 for two rescuers.

- Procedure:

- Confirm unresponsiveness, check for breathing and pulse simultaneously (max 10 seconds).

- If no pulse, begin compressions immediately. Attach the AED as soon as it is available.

- Check for a pulse again only when the AED advises or after 5 cycles (2 minutes) of CPR.

- Complications: Fractured ribs, fractured sternum, and lacerated liver are possible but should not deter high-quality compressions.

Automated External Defibrillator (AED)

- Indications: Any patient who is unresponsive and pulseleless.

- Shockable Rhythms:

- Ventricular Fibrillation (V-Fib): Disorganized, chaotic electrical activity.

- Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (V-Tach): Rapid, organized electrical activity from the ventricles that is too fast to allow the heart to fill, producing no pulse.

- Non-Shockable Rhythms:

- Asystole: Flatline; no electrical activity.

- Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA): Organized electrical activity is present, but the heart muscle does not contract or respond.

- AED Special Considerations:

- Pacemakers: Do not place pads directly over a pacemaker. Place them at least one inch away.

- Medication Patches: Remove any transdermal patches and wipe the area clean before applying pads.

- Hairy Chest: If pads do not adhere, quickly shave the area or use a second set of pads to “wax” the area by applying and quickly ripping them off.

- Water: Remove the patient from standing water. A small puddle or snow is acceptable if the chest is wiped dry.

- Moving Vehicle: The vehicle MUST be stopped for the AED to analyze the rhythm accurately and to ensure safety during a shock.

- Pediatric Use:

- Infants/Children < 8 years: A manual defibrillator is preferred. If unavailable, use an AED with a pediatric dose attenuator. If neither is available, an adult AED may be used as a last resort.

Return of Spontaneous Circulation (ROSC)

- Signs of ROSC: The patient regains a palpable pulse or there is a sudden, sustained increase in end-tidal CO2 (PETCO2).

- Post-ROSC Care:

- Manage the airway. Provide assisted ventilations via BVM at a rate of 10-12 breaths per minute (1 breath every 5-6 seconds) to maintain an oxygen saturation of 92-98%.

- Perform a neurological exam.

- Obtain and transmit a 12-lead ECG if available.

- Monitor vital signs closely and prepare for transport.

Transport & Termination Decisions

- Begin Transport When:

- ROSC occurs.

- 6–9 shocks have been delivered and the patient remains in arrest.

- The AED gives 3 consecutive “no shock advised” messages separated by CPR cycles.

- Termination of Efforts (Considered by ALS/Medical Control):

- Arrest was not witnessed by EMS.

- No AED shock was ever delivered.

- No ROSC was achieved in the field.

Part 4: Pharmacological Interventions

The 6 Rights of Medication Administration

- Right Patient

- Right Medication

- Right Dose

- Right Route

- Right Time (Indication & Expiration Date)

- Right Documentation

Common Cardiac Medications

- Oxygen: Administer to maintain target saturation levels:

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): >90%

- Stroke: 95-98%

- Post-Cardiac Arrest: 92-98%

- Aspirin (ASA):

- Action: Inhibits platelet aggregation (prevents platelets from clumping together to form clots).

- Indication: Chest pain suggestive of cardiac ischemia.

- Dose: 162–325 mg (2–4 low-dose tablets). Must be chewed.

- Contraindications: Allergy, history of bleeding disorders, recent GI bleed, liver damage. Should not be given to children (risk of Reye’s syndrome).

- Nitroglycerin (NTG):

- Action: Vasodilator; it relaxes blood vessels, which decreases the workload on the heart and increases blood flow to the myocardium.

- Indication: Chest pain in a patient with a prescription for nitroglycerin.

- Dose: One tablet or spray (0.4 mg) sublingually. Can be repeated every 5 minutes up to 3 doses if pain persists and criteria are met.

- CRITICAL Contraindications:

- Systolic BP less than 100 mmHg.

- Use of erectile dysfunction medications (sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) within the past 48 hours.

- Head injury.

- Bradycardia (HR < 50) or Tachycardia (HR > 110).

- Side Effects: Headache, hypotension, burning under the tongue.

Order of Operations for Chest Pain: Place the patient in a position of comfort, administer oxygen if indicated, assist with Aspirin, and then assist with Nitroglycerin if criteria are met.

Part 5: Pathophysiology of Specific Emergencies

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) & Myocardial Infarction (AMI)

- ACS: An umbrella term for any condition caused by a sudden reduction of blood flow to the heart (myocardial ischemia).

- Angina Pectoris: Chest pain caused by temporary ischemia.

- Stable Angina: Occurs with exertion and is relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

- Unstable Angina: Occurs at rest or is unpredictable. It is a sign of an impending heart attack.

- Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) / Heart Attack: The death of myocardial tissue due to a complete blockage of a coronary artery. The pain is not relieved by rest or nitro and can last for hours. The left ventricle is most commonly affected.

- Symptoms of ACS/AMI:

- Chest pain/pressure/heaviness (often described as “crushing” or “squeezing”).

- Pain radiating to the jaw, arms (especially the left), back, or abdomen.

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath).

- Diaphoresis (sweating), weakness, nausea/vomiting.

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)

A condition where the heart muscle is damaged and cannot pump effectively, leading to a backup of blood in the circulatory system.

- Left-Sided CHF: The left ventricle fails, causing blood to back up into the lungs.

- Signs: Pulmonary edema, dyspnea (especially when lying flat), hypoxia, crackles (rales) in the lungs, and sometimes pink, frothy sputum.

- Right-Sided CHF: The right ventricle fails, causing blood to back up in the systemic circulation.

- Signs: Jugular Vein Distention (JVD), peripheral edema (swelling in the feet and legs), and abdominal distention (ascites).

Other Major Vascular Emergencies

- Aortic Aneurysm/Dissection: A tear in the inner layer of the aorta allows blood to flow between the layers of the vessel wall. It is most often caused by uncontrolled hypertension.

- Symptom: Sudden onset of a “sharp” or “tearing” chest pain that radiates to the back or shoulder blades. This is a true emergency requiring immediate transport; Aspirin and Nitro are contraindicated.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): A blockage in the pulmonary arteries, usually from a blood clot that traveled from the legs (DVT).

- Symptoms: Sudden onset of dyspnea, sharp (pleuritic) chest pain, tachycardia, and hypoxia.

- Hypertensive Emergency: A sudden, severe elevation in blood pressure (systolic > 180 and/or diastolic > 120) that can cause organ damage.

- Symptoms: Severe headache, strong bounding pulse, dizziness, and possibly pulmonary edema.

Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA) / Stroke

An interruption of blood flow to an area of the brain.

- Ischemic Stroke (85%): Caused by a blockage (thrombus or embolus).

- Hemorrhagic Stroke (15%): Caused by bleeding within the brain tissue.

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): “Mini-stroke” where symptoms resolve on their own. It is a major warning sign of a future stroke.

- Signs of Stroke: Facial droop, arm drift, slurred speech, sudden vision changes, difficulty walking.

- Stroke Mimics: Hypoglycemia, postictal state after a seizure, alcohol intoxication. Always check a blood glucose level.

Cardiac Tamponade

Fluid or blood fills the pericardial sac, compressing the heart and preventing it from filling properly. This leads to obstructive shock.

- Beck’s Triad: The classic signs of cardiac tamponade:

- Hypotension (due to decreased cardiac output).

- Jugular Venous Distention (JVD) (due to blood backing up).

- Muffled Heart Sounds (due to the fluid insulating the sound).

Part 6: Shock (Hypoperfusion)

Shock is a state of circulatory collapse resulting in inadequate cellular perfusion.

Stages of Shock

- Compensated Shock (Early): The body is still able to compensate by increasing heart rate and constricting blood vessels.

- Signs: Anxiety, restlessness, altered mental status, rapid/thready pulse, cool/clammy skin, narrowing pulse pressures.

- Decompensated Shock (Late): The body’s compensatory mechanisms are failing.

- Signs: Falling blood pressure (hypotension is a late and ominous sign), labored/irregular breathing, dull eyes/dilated pupils, ashen/mottled/cyanotic skin.

Types of Shock

- Hypovolemic Shock: Caused by a loss of blood or fluid (e.g., hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea). Signs include tachycardia, rapid weak pulse, cool clammy skin, and hypotension.

- Cardiogenic Shock: Caused by heart failure (pump failure), often after an AMI. Signs are similar to hypovolemic shock but may also include pulmonary edema.

- Obstructive Shock: Caused by a physical blockage of blood flow.

- Causes: Tension pneumothorax, Cardiac Tamponade, Pulmonary Embolism.

- Distributive Shock: Caused by widespread vasodilation, leading to a relative loss of fluid volume.

- Septic Shock: From severe infection. Presents with fever and warm skin initially.

- Neurogenic Shock: From spinal cord injury. Presents with bradycardia, hypotension, and warm/dry skin below the level of the injury.

- Anaphylactic Shock: From a severe allergic reaction. Presents with hives, wheezing, and hypotension.

- Psychogenic Shock: Fainting (syncope) from a temporary vasodilation that reduces blood flow to the brain.

Key Shock-Related Syndromes

- Cushing’s Triad: Indicates severely elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), often from a head injury. It is the opposite of shock.

- Hypertension (with a widening pulse pressure).

- Bradycardia.

- Irregular Respirations (e.g., Cheyne-Stokes).

- Cheyne-Stokes Respirations: A breathing pattern of progressively deeper and faster breathing, followed by a gradual decrease that results in a temporary stop in breathing (apnea). It is a sign of brainstem injury or severe CHF.